- Bandana

- Posts

- Issue #34

Issue #34

Japan’s Noren Are Having a Style Moment

Words by Cory Ohlendorf | Photography courtesy of AKASHI-KAMA

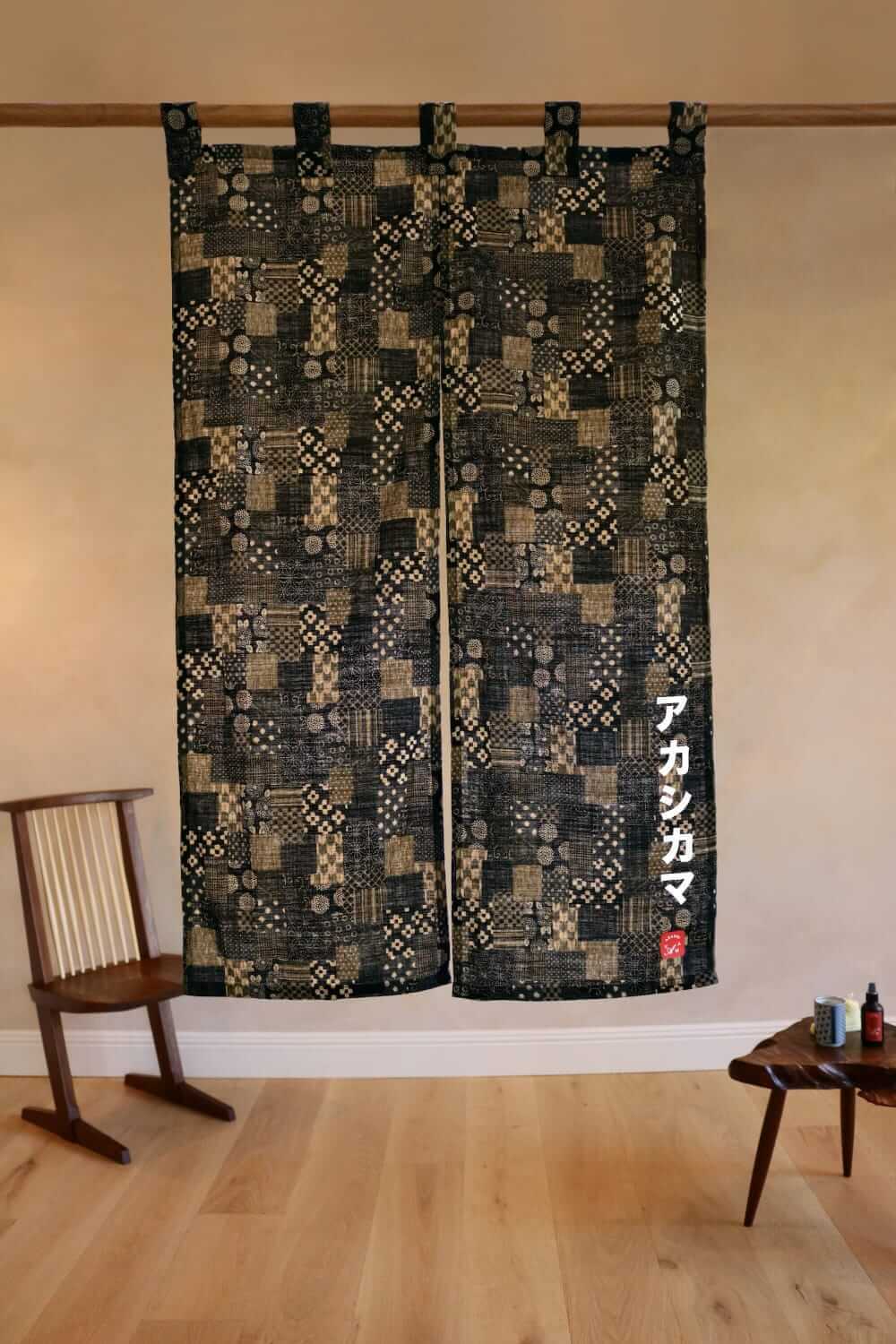

There are some things that are absolutely, undeniably, quintessentially Japanese. And the noren (暖簾) is one of them. The humble fabric curtain—often draped gracefully across a shop or restaurant entrance or even in homes—has deep cultural, historical and artistic significance.

Whether walking into traditional shops in Kyoto, visiting an old school onsen or ducking into a Tokyo ramen shop, you’ve likely brushed past a noren without even realizing its significance. These short fabric curtains, often split into two or more sections with vertical cuts that promote airflow and encourage passage, are hung in doorways to signal everything from “we’re open” to “welcome home”.

But noren are more than just practical—they're a deeply symbolic and surprisingly personal part of Japanese culture. The curtains have existed in Japan since the early Heian period (794–1185). Initially, they were purely functional. Noren protected your interiors from sunlight, wind, dust and unwanted eyes. By the Kamakura period (1185–1333), they began to feature central motifs or family crests. And by the Edo period, they had evolved into brand identifiers, a kind of visual signage and early form of branding, proudly displaying the markings of the business. What’s more, a weathered noren had its own design language: it communicated that we’ve been here a while, and we know what we’re doing.

And in 2025, noren are having something of a renaissance. As Japan's appreciation for traditional craftsmanship intersects with global interest in slow living and curated interiors, noren are popping up in new places—stylish homes, boutique hotels, even coworking spaces. In small Tokyo apartments, noren now separate spaces without closing them off. In modern ryokans, a sheer noren might replace a bathroom door or simply serve as a piece of soft, tactile art.

AKASHI-KAMA, the California-based brand known for its modern interpretations of classic Japanese noragi jackets (I personally own three), has just released a second run of their noren. Founder Alec Nakashima tells me that he always wanted to get into home and decor, and this felt like the perfect way for them to do so. |

“It started with the thought exercise: ‘What constitutes a modern heirloom?’ Norens had so much function—gently separating spaces in past eras—I think a lot of our homes can use that today. We still wanted them to be versatile, so they are designed to work in doorways (the traditional use) or as wall art (a more modern use).” He calls it a “perfect distillation of our brand,” something that blends the traditional with a more contemporary approach. “These were fully handcrafted in the northern prefecture of Iwate with a 5th generation factory, and we obsessed over the details—from the textured logos to the top tabs.”

Today, you can find noren of varying quality and designs, from modern brands like Buaisou, offering intricate indigo-dyed noren in deep shades of blue, to speciality shops like Nishimura Shōten, which was founded in 1910 and specializes in custom designs. They’ve become quiet status symbols too. A custom noren designed by a local artisan can cost as much as a made-to-measure suit. And in the age of Instagram, their elegance and motion are tailor-made for soft, cinematic posts—one gentle breeze and you're in a hazy zen dreamscape. |

For a culture that places such emphasis on thresholds—between outside and in, public and private—the noren remains a subtle but powerful symbol. It’s where hospitality meets heritage. And in a world that often favors flash over meaning, this simple curtain proves that tradition still has the power to turn heads.

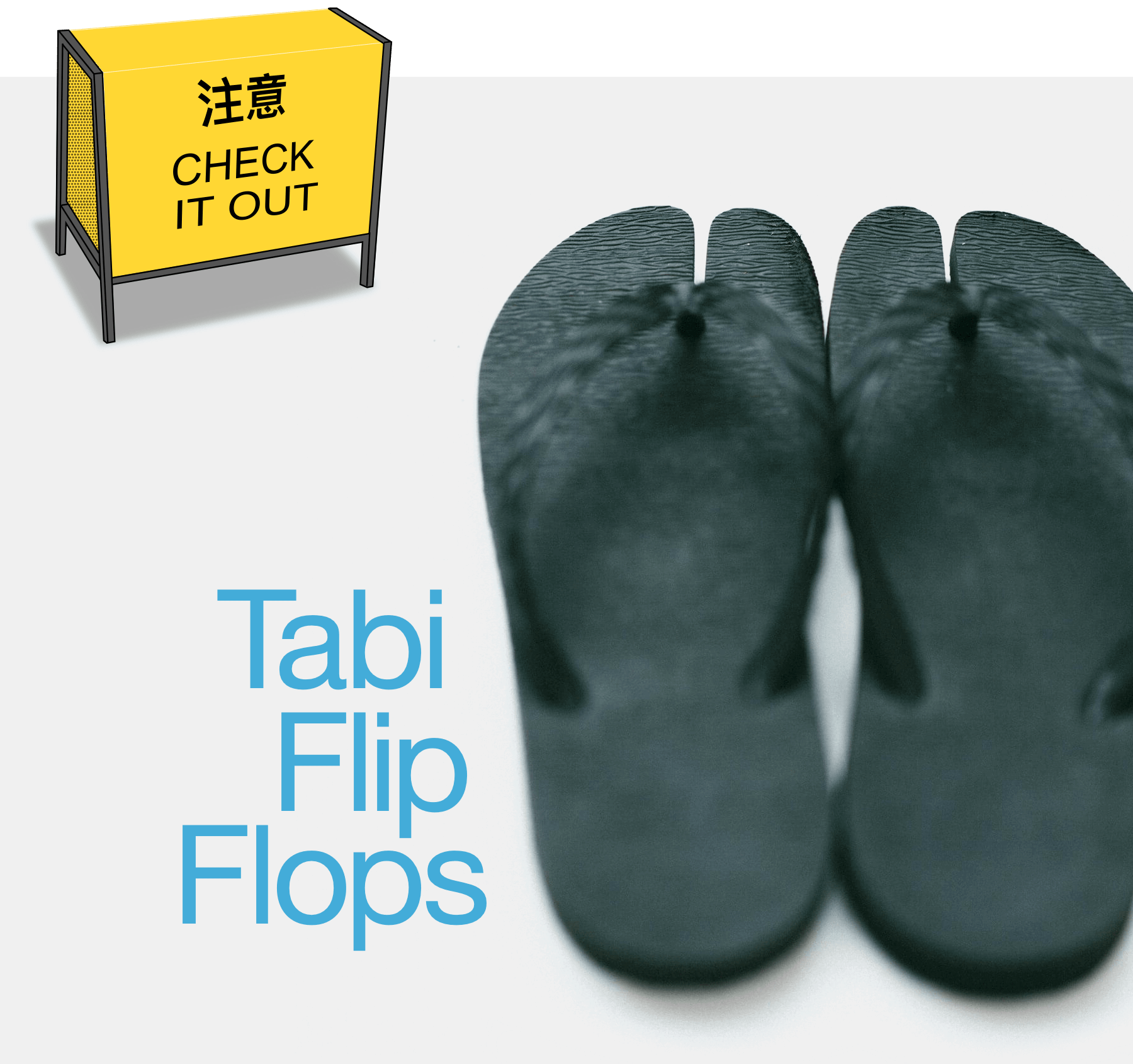

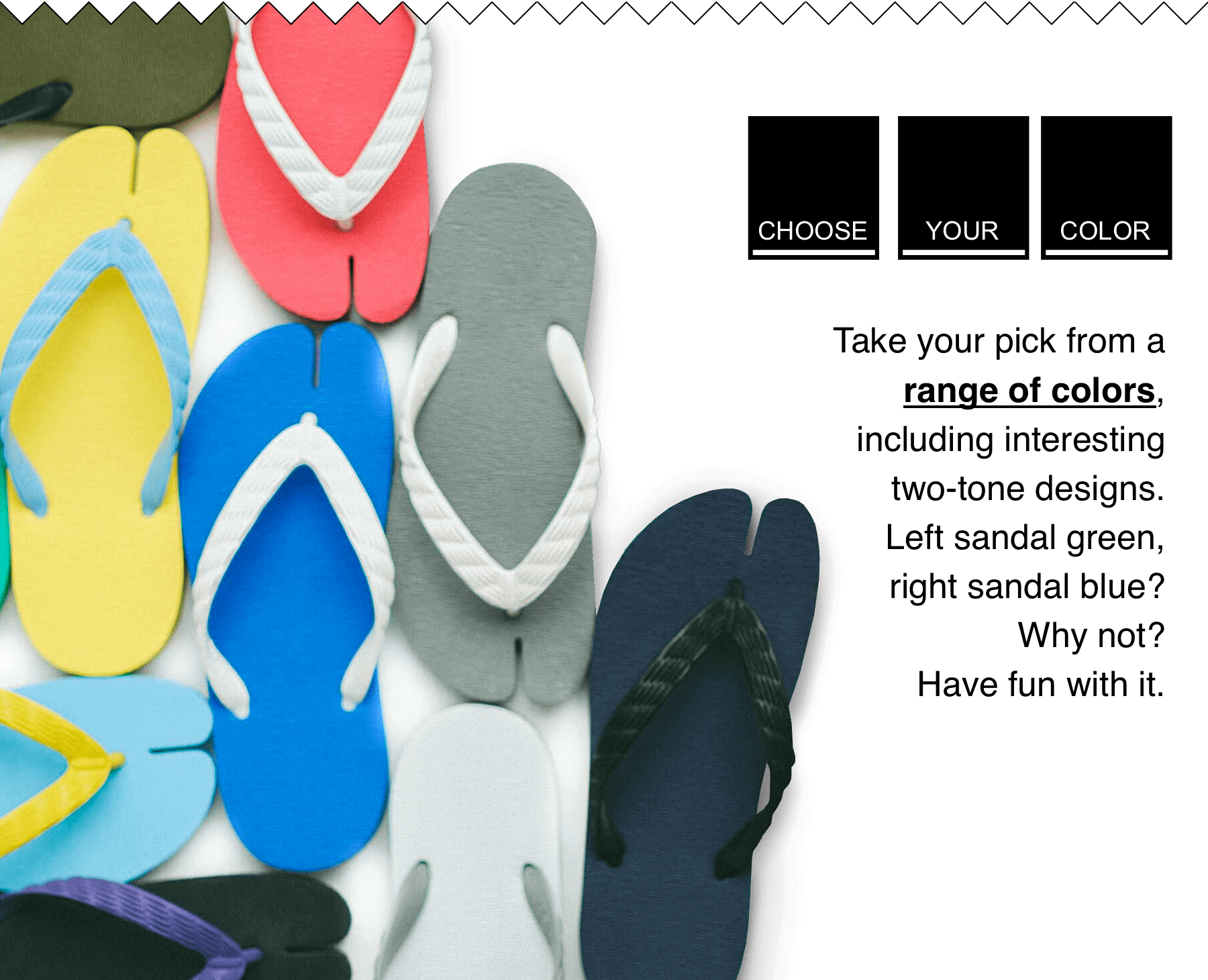

Margiela is not the only label making modern tabis. Discover the playful charm of SOU・SOU’s Deportare Beach Sandals (Sen’nichi Tabi)—a breezy flip-flop reimagined with a traditional Japanese split-toe design. Each one is hand-crafted by Tsukumo Co., one of the few domestic beach sandals factories in Japan. Made with durable synthetic rubber soles and natural rubber thongs, they offer a lightweight and fresh twist on classic Japanese footwear with unmistakable personality and reliable comfort.

Get It | Tabi rubber sandals, $19.50 by SOU・SOU |

The Japanese phrase yo no bi (用美) translates to the “beauty of use” or "beauty in function". It refers to the aesthetic appreciation of objects that are both practical and beautiful, often implying a sense of harmony between form and function in everyday items. It’s a concept that refers not only to the beauty of the crafts themselves, but also to a beauty inherent in their usefulness in daily life. As our lives have become filled with efficient and convenient digital appliances and smartphones, there remains an appreciation for something that’s practical and simple yet still gets the job done.

Start at |

Mori Art Museum  |

Grab a CoffeeIt might be too hot to relax in an open-air bath, but you can get old school sento vibes at this former bathhouse-turned-cafe. Miyano-yu offers up tasty homemade sweets, shaved iced with fruit, craft beers, and, of course, iced coffee. Miyano-yu  |

Have a |

Koukian |

That’s all

for this week.

We’ll see you back here next Thursday.

Know someone that would like Bandana? |